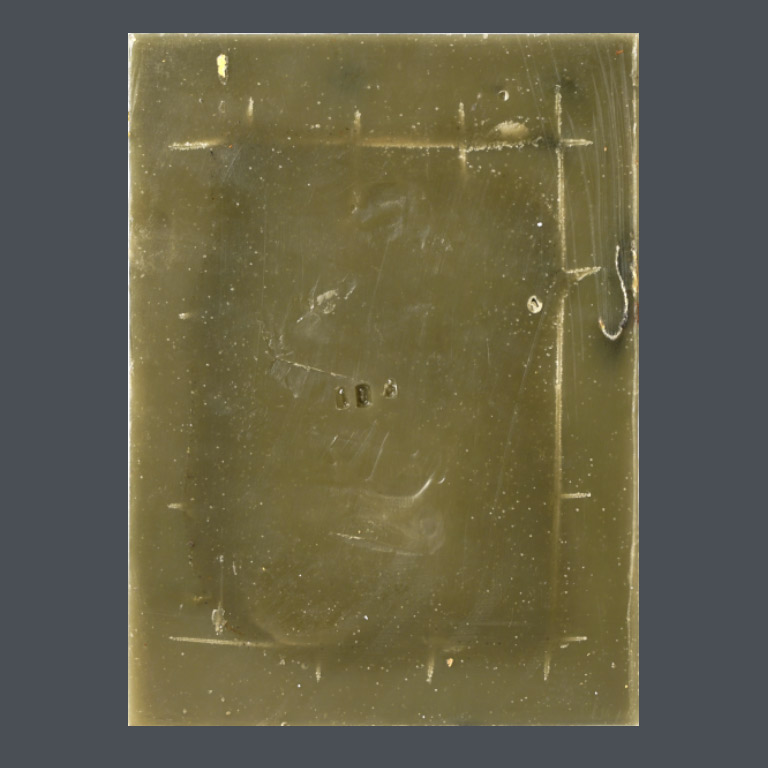

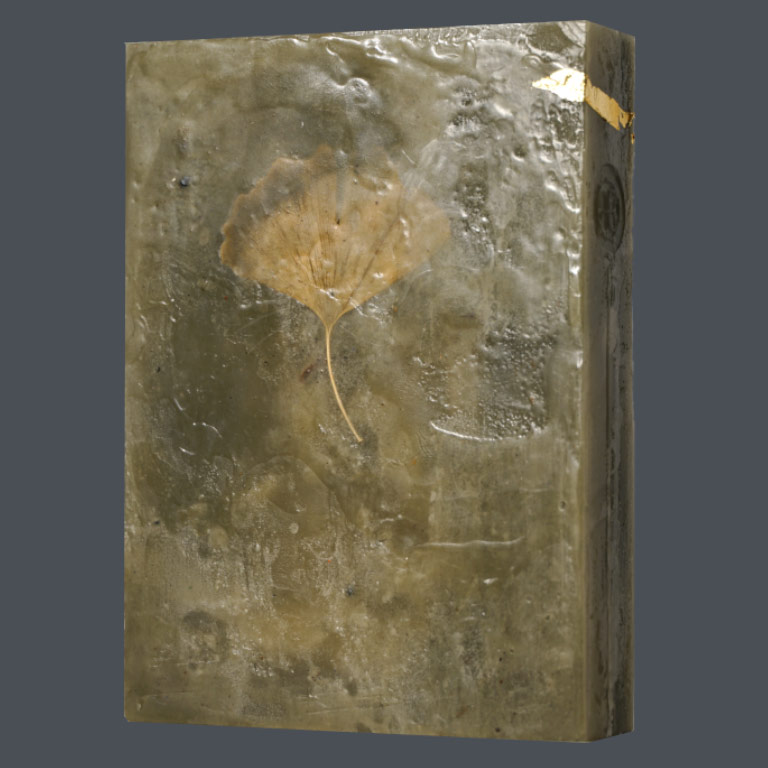

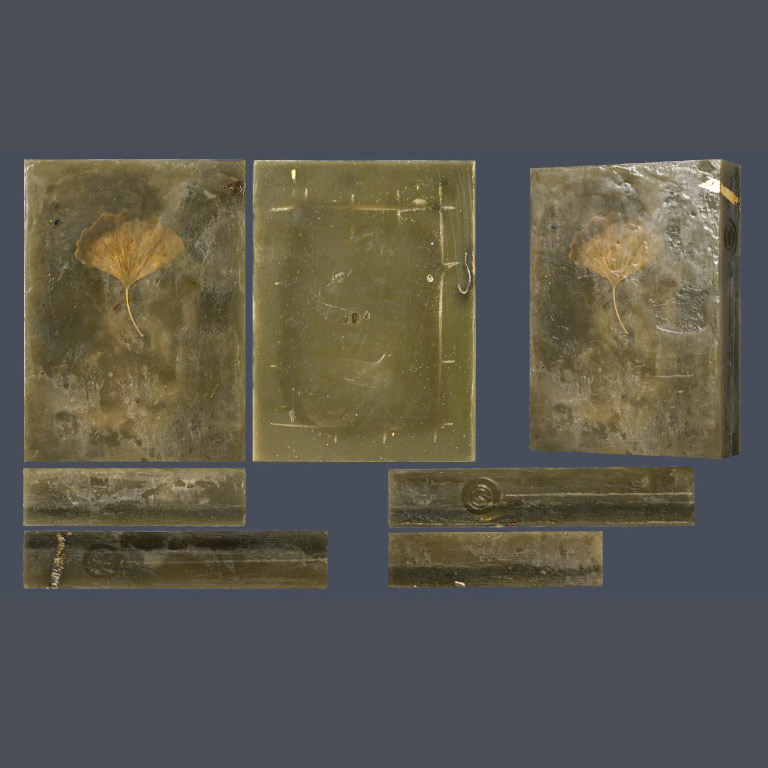

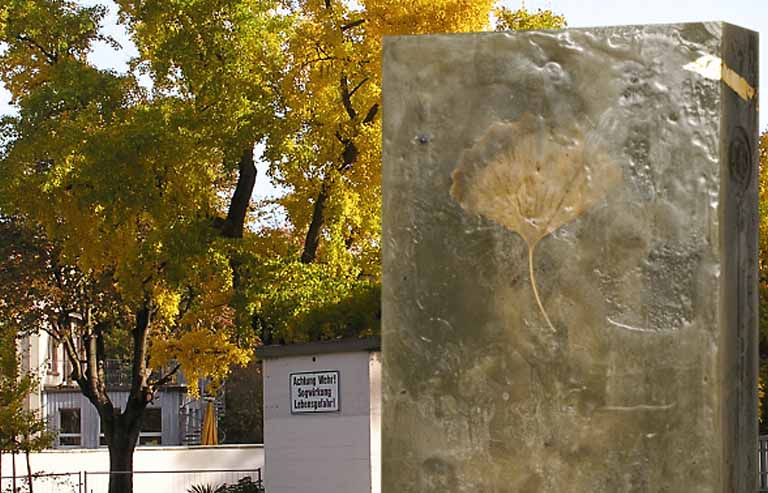

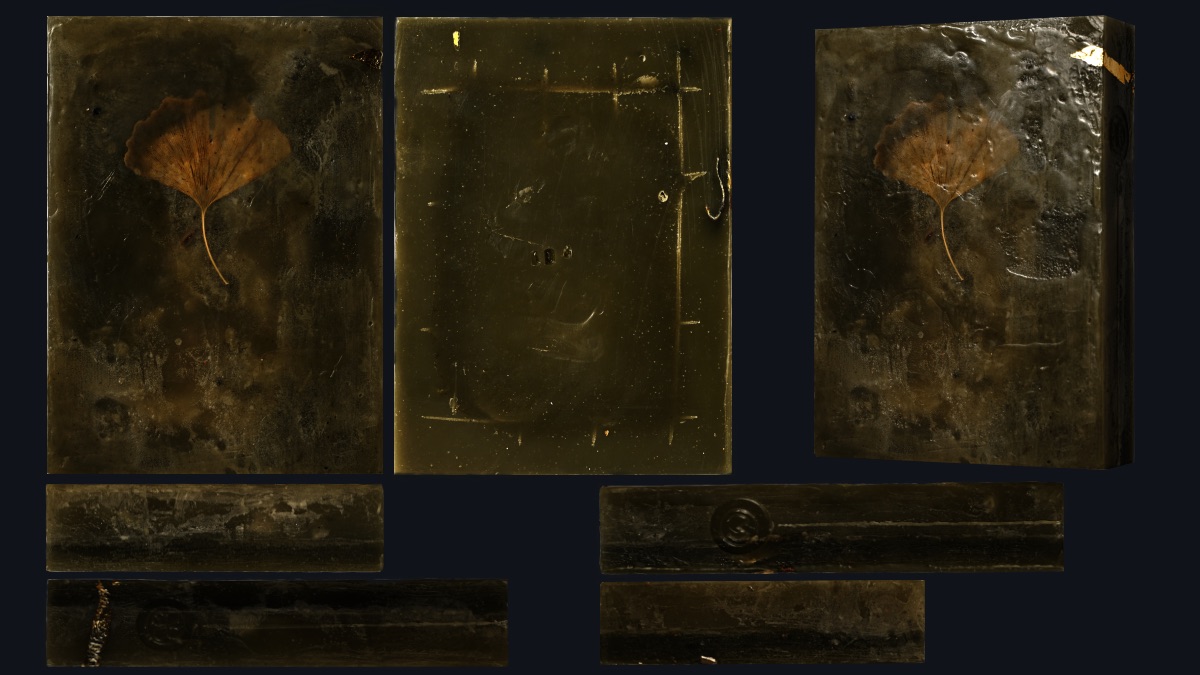

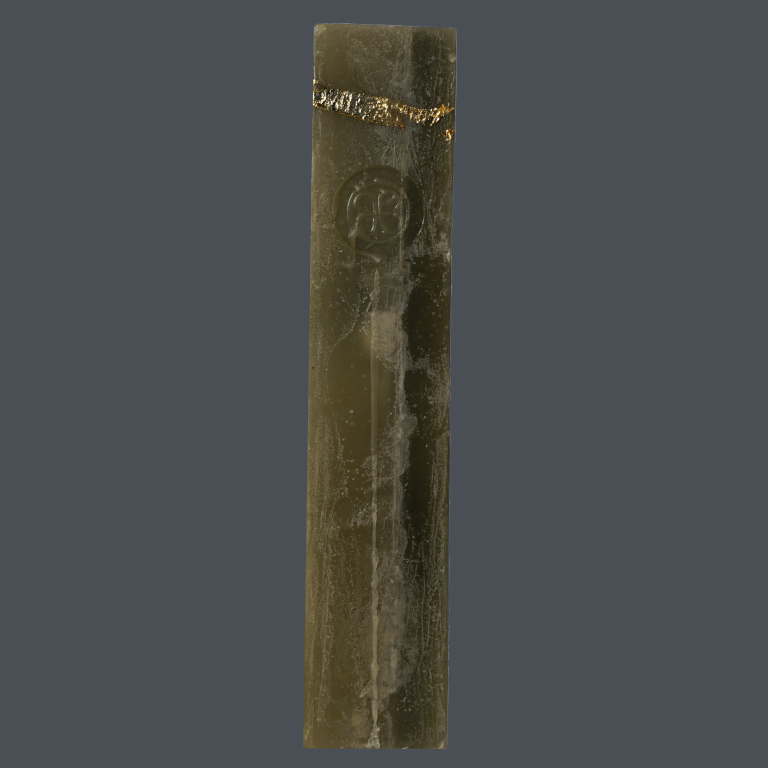

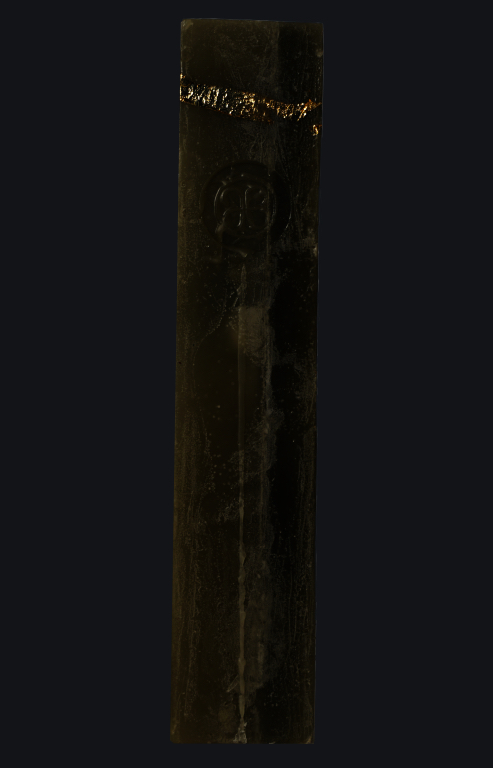

#103 Sides 1-7

Ginkgo biloba

Ginkgo biloba, commonly known as ginkgo or gingko (both pronounced /ˈɡɪŋkoʊ/), also known as the ginkgo tree or the maidenhair tree, is the only living species in the division Ginkgophyta, all others being extinct. It is found in fossils dating back 270 million years. Native to China, the tree is widely cultivated and was introduced early to human history. It has various uses in traditional medicine and as a source of food. The genus name Ginkgo is regarded as a misspelling of the Japanese gin kyo, “silver apricot”.

Gingo Biloba by JWG (translation)

This tree’s leaf, that from the East,

Has been entrusted to my garden,

Gives to savor secret sense,

As pleasing the initiate.

Is it one living creature,

Which separated in itself?

Are they two, who choose themselves,

To be recognized as one?

Such query to reciprocate,

I surely found the proper use,

Do not you feel it in my songs,

That I am one and double?

Dieses Baums Blatt, der von Osten

Meinem Garten anvertraut,

Giebt geheimen Sinn zu kosten,

Wie’s den Wissenden erbaut,

Ist es Ein lebendig Wesen,

Das sich in sich selbst getrennt?

Sind es zwei, die sich erlesen,

Daß man sie als Eines kennt?

Solche Frage zu erwidern,

Fand ich wohl den rechten Sinn,

Fühlst du nicht an meinen Liedern,

Daß ich Eins und doppelt bin?

“Gingo biloba” (later: “Ginkgo biloba“) is a poem written by the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The poem was published in his work West-östlicher Diwan (West-Eastern Divan), first published in 1819. Goethe used “Gingo” instead of “Ginkgo” in the first version to avoid the hard sound of the letter “k”.

Goethe sent Marianne von Willemer (1784–1860), the wife of the Frankfurt banker Johann Jakob von Willemer (1760–1838), a Ginkgo leaf as a symbol of friendship and on September 15, 1815, he read his draft of the poem to her and friends. On September 23, 1815, he saw Marianne for the last time. Then he showed her the Ginkgo tree in the garden of Heidelberg Castle from which he took the two leaves pasted onto the poem. After that he wrote the poem and sent it to Marianne on September 27, 1815.

Directly across from the Ginkgo tree stands the Goethe memorial tablet. The poem was published later in the “Book of Suleika” in West-östlicher Diwan.

#103 Side 3

More...

Midas (/ˈmaɪdəs/; Greek: Μίδας) is the name of at least three members of the royal house of Phrygia.

The most famous King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ability to turn everything he touched into gold. This came to be called the golden touch, or the Midas touch. The Phrygian city Midaeum was presumably named after this Midas, and this is probably also the Midas that according to Pausanias founded Ancyra. According to Aristotle, legend held that Midas died of starvation as a result of his “vain prayer” for the gold touch. The legends told about this Midas and his father Gordias, credited with founding the Phrygian capital city Gordium and tying the Gordian Knot, indicate that they were believed to have lived sometime in the 2nd millennium BC, well before the Trojan War. However, Homer does not mention Midas or Gordias, while instead mentioning two other Phrygian kings, Mygdon and Otreus.

Another King Midas ruled Phrygia in the late 8th century BC, up until the sacking of Gordium by the Cimmerians, when he is said to have committed suicide. Most historians believe this Midas is the same person as the Mita, called king of the Mushkiin Assyrian texts, who warred with Assyria and its Anatolian provinces during the same period.

A third Midas is said by Herodotus to have been a member of the royal house of Phrygia and the grandfather of an Adrastus, who fled Phrygia after accidentally killing his brother and took asylum in Lydia during the reign of Croesus. Phrygia was by that time a Lydian subject. Herodotus says that Croesus regarded the Phrygian royal house as “friends” but does not mention whether the Phrygian royal house still ruled as (vassal) kings of Phrygia.

There are many, and often contradictory, legends about the most ancient King Midas. In one, Midas was king of Pessinus, a city of Phrygia, who as a child was adopted by King Gordias and Cybele, the goddess whose consort he was, and who (by some accounts) was the goddess-mother of Midas himself. Some accounts place the youth of Midas in Macedonian Bermion (See Bryges) In Thracian Mygdonia, Herodotus referred to a wild rose garden at the foot of Mount Bermion as “the garden of Midas son of Gordias, where roses grow of themselves, each bearing sixty blossoms and of surpassing fragrance”. Herodotus says elsewhere that Phrygians anciently lived in Europe where they were known as Bryges, and the existence of the garden implies that Herodotus believed that Midas lived prior to a Phrygian migration to Anatolia.

According to some accounts, Midas had a son, Lityerses, the demonic reaper of men, but in some variations of the myth he instead had a daughter, Zoë or “life”. According to other accounts he had a son Anchurus.

Arrian gives an alternative story of the descent and life of Midas. According to him, Midas was the son of Gordios, a poor peasant, and a Telmissian maiden of the prophetic race. When Midas grew up to be a handsome and valiant man, the Phrygians were harassed by civil discord, and consulting the oracle, they were told that a wagon would bring them a king, who would put an end to their discord. While they were still deliberating, Midas arrived with his father and mother, and stopped near the assembly, wagon and all. They, comparing the oracular response with this occurrence, decided that this was the person whom the god told them the wagon would bring. They therefore appointed Midas king and he, putting an end to their discord, dedicated his father’s wagon in the citadel as a thank-offering to Zeus the king. In addition to this the following saying was current concerning the wagon, that whosoever could loosen the cord of the yoke of this wagon, was destined to gain the rule of Asia. This someone was to be Alexander the Great. In other versions of the legend, it was Midas’ father Gordias who arrived humbly in the cart and made the Gordian Knot.

Herodotus said that a “Midas son of Gordias” made an offering to the Oracle of Delphi of a royal throne “from which he made judgments” that were “well worth seeing”, and that this Midas was the only foreigner to make an offering to Delphi before Gyges of Lydia. The historical Midas of the 8th century BC and Gyges are believed to have been contemporaries, so it seems most likely that Herodotus believed that the throne was donated by the earlier, legendary King Midas. However, some historians believe that this throne was donated by the later, historical King Midas.

Golden Touch

One day, as Ovid relates in Metamorphoses XI, Dionysus found that his old schoolmaster and foster father, the satyr Silenus, was missing. The old satyr had been drinking wine and wandered away drunk, to be found by some Phrygian peasants who carried him to their king, Midas (alternatively, Silenus passed out in Midas’ rose garden). Midas recognized him and treated him hospitably, entertaining him for ten days and nights with politeness, while Silenus delighted Midas and his friends with stories and songs. On the eleventh day, he brought Silenus back to Dionysus in Lydia. Dionysus offered Midas his choice of whatever reward he wished for. Midas asked that whatever he might touch should be changed into gold.

Midas rejoiced in his new power, which he hastened to put to the test. He touched an oak twig and a stone; both turned to gold. Overjoyed, as soon as he got home, he touched every rose in the rose garden, and all became gold. He ordered the servants to set a feast on the table. “So Midas, king of Lydia, swelled at first with pride when he found he could transform everything he touched to gold; but when he beheld his food grow rigid and his drink harden into golden ice then he understood that this gift was a bane and in his loathing for gold, cursed his prayer” (Claudian, In Rufinem).

In a version told by Nathaniel Hawthorne in A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1852), Midas’ daughter came to him, upset about the roses that had lost their fragrance and become hard, and when he reached out to comfort her, found that when he touched his daughter, she turned to gold as well. Now, Midas hated the gift he had coveted. He prayed to Dionysus, begging to be delivered from starvation. Dionysus heard his prayer, and consented; telling Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. Then, whatever he put into the water would be reversed of the touch.

Midas did so, and when he touched the waters, the power flowed into the river, and the river sands turned into gold. This explained why the river Pactolus was so rich in gold, and the wealth of the dynasty claiming Midas as its forefather no doubt the impetus for this aetiological myth. Gold was perhaps not the only metallic source of Midas’ riches: “King Midas, a Phrygian, son of Cybele, first discovered black and white lead”.

Ears of a Donkey

Midas, now hating wealth and splendor, moved to the country and became a worshipper of Pan, the god of the fields and satyr. Roman mythographers asserted that his tutor in music was Orpheus.

Once, Pan had the audacity to compare his music with that of Apollo, and challenged Apollo to a trial of skill (also see Marsyas). Tmolus, the mountain-god, was chosen as umpire. Pan blew on his pipes and, with his rustic melody, gave great satisfaction to himself and his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present. Then Apollo struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo, and all but one agreed with the judgment. Midas dissented, and questioned the justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any longer, and said “Must have ears of an ass!”, which caused Midas’s ears to become those of a donkey. The myth is illustrated by two paintings, “Apollo and Marsyas” by Palma il Giovane (1544–1628), one depicting the scene before, and one after, the punishment. Midas was mortified at this mishap. He attempted to hide his misfortune under an ample turban or headdress, but his barber of course knew the secret, so was told not to mention it. However, the barber could not keep the secret; he went out into the meadow, dug a hole in the ground, whispered the story into it, then covered the hole up. A thick bed of reeds later sprang up in the meadow, and began whispering the story, saying “King Midas has an ass’ ears”. Some sources said that Midas killed himself by drinking the blood of an ox.

Sarah Morris demonstrated (Morris 2004) that donkeys’ ears were a Bronze Age royal attribute, borne by King Tarkasnawa (Greek Tarkondemos) of Mira, on a seal inscribed in both Hittite cuneiform and Luwian hieroglyphs: in this connection, the myth would appear for Greeks to justify the exotic attribute.

Similar myths in other cultures

In pre-Islamic legend of Central Asia, the king of the Ossounes of the Yenisei basin had donkey’s ears. He would hide them, and order each of his barbers murdered to hide his secret. The last barber among his people was counselled to whisper the heavy secret into a well after sundown, but he didn’t cover the well afterwards. The well water rose and flooded the kingdom, creating the waters of Lake Issyk-Kul.

According to an Irish legend, the king Labraid Loingsech had horse’s ears, something he was concerned to keep quiet. He had his hair cut once a year, and the barber, who was chosen by lot, was immediately put to death. A widow, hearing that her only son had been chosen to cut the king’s hair, begged the king not to kill him, and he agreed, so long as the barber kept his secret. The burden of the secret was so heavy that the barber fell ill. A druid advised him to go to a crossroads and tell his secret to the first tree he came to, and he would be relieved of his burden and be well again. He told the secret to a large willow. Soon after this, however, a harper named Craiftine broke his instrument, and made a new one out of the very willow the barber had told his secret to. Whenever he played it, the harp sang “Labraid Lorc has horse’s ears”. Labraid repented of all the barbers he had put to death and admitted his secret.

#103 Side 4

More...

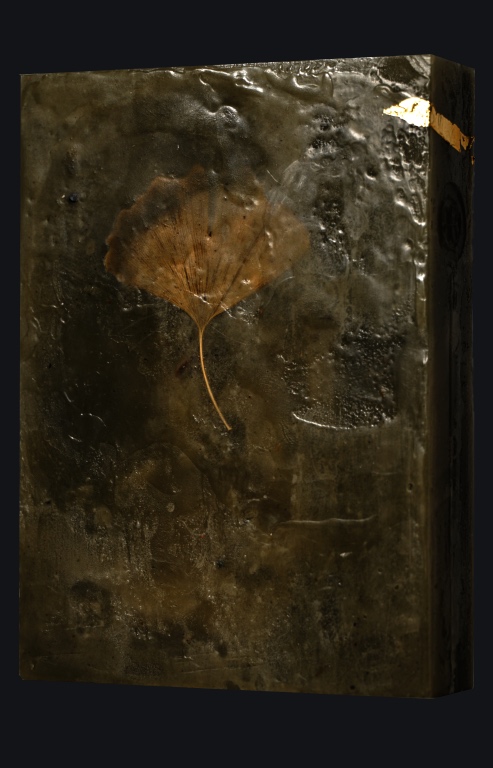

Encaustic painting, also known as hot wax painting, involves using heated beeswax to which colored pigments are added. The liquid or paste is then applied to a surface—usually prepared wood, though canvas and other materials are often used. The simplest encaustic mixture can be made from adding pigments to beeswax, but there are several other recipes that can be used—some containing other types of waxes, damar resin, linseed oil, or other ingredients. Pure, powdered pigments can be used, though some mixtures use oil paints or other forms of pigment.

Metal tools and special brushes can be used to shape the paint before it cools, or heated metal tools can be used to manipulate the wax once it has cooled onto the surface. Today, tools such as heat lamps, heat guns, and other methods of applying heat allow artists to extend the amount of time they have to work with the material. Because wax is used as the pigment binder, encaustics can be sculpted as well as painted. Other materials can be encased or collaged into the surface, or layered, using the encaustic medium to stick them to the surface.

#103 Side 5

More...

Aleppo soap (also known as savon d’Alep, laurel soap, Syrian soap, or ghar soap, the Syrian word for ‘laurel’) is a handmade, hard bar soap associated with the city of Aleppo, Syria. Aleppo soap is classified as a Castile soap as it is a hard soap made from olive oil and lye, from which it is distinguished by the inclusion of laurel oil.

Aleppo soap (also known as savon d’Alep, laurel soap, Syrian soap, or ghar soap, the Syrian word for ‘laurel’) is a handmade, hard bar soap associated with the city of Aleppo, Syria. Aleppo soap is classified as a Castile soap as it is a hard soap made from olive oil and lye, from which it is distinguished by the inclusion of laurel oil.

The origin of Aleppo soap is unknown. Unverified claims of its great antiquity abound, such as its supposed use by Queen Cleopatra of Egypt and Queen Zenobia of Syria. It is commonly thought that the process of soap-making emanated from the Levant region (of which Aleppo is a main city) and to have moved west from there to Europe after the first Crusades. This is based on the claim that the earliest soap made in Europe was shortly after the Crusades, but soap was known to the Romans in the first century AD and Zosimos of Panopolis described soap and soapmaking in ca. 300 AD.

Today most Aleppo soap, especially that containing more than 16% of laurel oil, is exported to Europe and East Asia.

Traditional Aleppo soap (Ghar) is made by the “hot process”.

First, the olive oil is brought into a large, in-ground vat along with water and lye. Underneath the vat, there is an underground fire which heats the contents to a boil. Boiling lasts three days while the oil reacts with the lye and water to become a thick liquid soap. The laurel oil is added at the end of the process, and after it is mixed in, the mix is taken from the vat and poured over a large sheet of waxed paper on the floor of the factory.

At this point the soap is a large, green, flat mass, and it is allowed to cool down and harden for about a day. While the soap is cooling, workers with planks of wood strapped to their feet walk over the soap to try to smooth out the batch and make it an even thickness.

The soap is then cut; three workers drag a rake-like cutting device through the soap to cut it one way, then again the other way until the whole mass is cut into individual cubes. Each cube is stamped with the soap artisan’s name.

The cubes of soap are then stacked in staggered cylinders to allow maximum air exposure. Once they have dried sufficiently, they are put into a special subterranean chamber to be aged for six months to a year.

While it is aging, the soap goes through several chemical changes. First, and most importantly, the free alkaline content of the soap (the alkaline which did not react with the oil during saponification) breaks down upon slow reaction with air. The moisture content of the soap is also reduced, making the soap hard and long lasting. And lastly, the color of the outside of the soap turns a pale gold, while the inside remains green.

Modern Aleppo soaps are manufactured using a “cold process” and contain olive and laurel oils, and may contain a variety of herbs and/or essential oils.

Traditional Aleppo soap is made with olive oil, laurel berry oil, water and lye, while the relative concentration of laurel oil (typically 2–30%) determines the quality and cost of the soap. Laurus nobilis, from which the berries come, is categorized as an underutilized species. As it is produced only from natural oils, Aleppo soap is also biodegradable.

In the 20th century, with the introduction of cold process soap making, Allepian soap artisans began introducing a variety of herbs and essential oils to their soaps.

Unlike most soaps, Aleppo soap will float in water.

Aleppo soap can be used daily as soap for washing and shampooing, as face mask, as shaving cream, and for bathing infants and babies. Laurel oil is an effective cleanser, antibiotic, anti-fungal and anti-itching agent.

Excerpt from /more at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleppo_soap

- Notice—For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do that is with a link to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

#103 Side 6

More...

The Battle of Aleppo (Arabic: معركة حلب) was a major military confrontation in Aleppo, the largest city in Syria, between the Syrian opposition (including the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and other Sunnigroups, such as the Levant Front and the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Al-Nusra Front), against the government of Bashar al-Assad, supported by Hezbollah, Shia militias and Russia, and against the Kurdish People’s Protection Units. The battle began on 19 July 2012 and was part of the ongoing Syrian Civil War. A stalemate that had been in place for four years finally ended in July 2016, when Syrian government troops closed the rebels’ last supply line into Aleppo with the support of Russian airstrikes. In response, rebel forces launched unsuccessful counteroffensives in September and October that failed to break the siege; in November, government forces embarked on a decisive campaign that resulted in the recapture of all of Aleppo by December 2016. The Syrian government victory was widely seen as a potential turning point in Syria’s civil war.

The large scale devastation of the battle and its importance led combatants to name it the “mother of battles” or “Syria’s Stalingrad”. The battle was marked by widespread violence against civilians, alleged repeated targeting of hospitals and schools (mostly by pro-government Air Forces and to a lesser extent by the rebels), and indiscriminate aerial strikes and shelling against civilian areas. It was also marked by the inability of the international community to resolve the conflict peacefully. The UN special envoy to Syria proposed to end the battle by giving East Aleppo autonomy, but the idea was rejected by the Syrian government. Hundreds of thousands of residents were displaced by the fighting and efforts to provide aid to civilians or facilitate evacuation were routinely disrupted by continued combat and mistrust between the opposing sides.

Various claims of war crimes emerged during the battle, including the use of chemical weapons by Syrian government forces as well as barrel bombs by the Syrian Air Force, the dropping of cluster munitions on populated areas by Russian and Syrian forces, the carrying out of “double tap” airstrikes to target rescue workers responding to previous strikes, and the use of highly inaccurate improvised artillery by rebel forces. During the 2016 Syrian government offensive, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that “crimes of historic proportions” were being committed in Aleppo.

Fighting also caused severe destruction to the Old City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage site. An estimated 33,500 buildings have been either damaged or destroyed. After four years of fighting, the battle represents one of the longest sieges in modern warfare and one of the bloodiest battles of the Syrian Civil War, leaving an estimated 31,000 people dead, almost a tenth of estimated overall war casualties.

Excerpt from /more at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Aleppo_(2012–2016)

- Notice—For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do that is with a link to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

The virtuality of values makes them a subject to choice. What kind of value system do WE want? Is the current system of organizing value working well? Is there any system at all? Anyhow, none of the human value system lasted as long as this tree, whose leave is the main subject also on this seventh side view.

The knowledge of survival

Hiroshima.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr, sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt ut labore et dolore magna aliquyam erat, sed diam voluptua.

Extreme examples of the ginkgo’s tenacity may be seen in Hiroshima, Japan, where six trees growing between 1–2 km from the 1945 atom bomb explosion were among the few living things in the area to survive the blast. Although almost all other plants (and animals) in the area were killed, the ginkgos, though charred, survived and were soon healthy again, among other hibakujumoku (trees that survived the blast).

The six trees are still alive: they are marked with signs at Housenbou (報専坊?) temple (planted in 1850), Shukkei-en (planted about 1740), Jōsei-ji (planted 1900), at the former site of Senda Elementary School near Miyukibashi, at the Myōjōin temple, and an Edo period-cutting at Anraku-ji temple.

The olive oil from the Mediterranean carries within its Latin name the adjective European. So this color is linked intrinsically with the history of European culture. It is a synonym for its traditions. When looking at one message out of Goethe’s East Western Divan, from which the Ging(k)o Biloba poem is taken, we start to understand that Eurasia isn’t to be divided in its parts even though this is a historic Anglo-American interest.